Boiling vs. Floating In the Ocean: How to Prioritize and Not Burn Out as a PM

Introduction - Service as Value

Early in my career as an investment banking analyst, my days were consumed by endless hours of tweaking financial models and creating slides for presentations. Among my experiences, one memory stands out vividly—developing a China strategy presentation for senior leaders. I toiled for countless hours drafting and revising over 100 slides – 40 for the actual presentation, and 60 for the appendix. However, as the presentation date approached, the main section was reduced to just 20 slides, relegating 80 to the appendix. When the printed deck made its debut, the painstakingly crafted appendix slides that I spent hundreds of hours on went unread, never to be referenced by anyone again.

The creation of pitch decks and presentations that clients never open is the unfortunate norm. Yet, this approach has persisted because, in professional services, value is measured in billable hours. One does whatever it takes to fulfill a client request, regardless of the impact of fulfilling that request or the human effort required to complete it.

Product Management - Product is Value

“Boiling the ocean” doesn’t work in tech, where the value lies in the products themselves. Unlike professional services, where additional client requests primarily impact the immediate working group, in product-focused companies, it affects multiple cross-functional teams and priorities, potentially resulting in incomplete tasks, overworked teams, and strained relationships. Therefore, in product-oriented companies, it is crucial to assess the impact versus the effort of adding new feature requests that can expand the scope of a product launch.

There are consequences to scope creep and not prioritizing. Unlike in investment banking and consulting, where projects have defined endpoints, software products do not have a clear “done.” While pitch decks and client presentations have a definitive "finish line" in the form of the client deliverable meeting, product management involves ongoing launches and iterative software improvements. If I have the team treat every “launch date” as a race, the team will burn out. The cost of prioritizing the wrong work is therefore “paid” by the entire company–in planning, designing, measuring, and ultimately maintaining a new project. Boiling the ocean is a lot more costly when you’re footing the bill.

But How Do You Prioritize?

So we create frameworks to ensure we’re working on the right thing. Concretely, we prioritize initiatives based on their RICE score – the reach, impact, confidence, and effort required for the upcoming launch and determine what can be deferred to a future release. Embracing a phased approach becomes crucial in creating clarity for the team regarding priorities within the evolving landscape of product development.

I learned about the RICE Framework from a mentor at my company and have found the framework valuable for prioritizing experiments and projects. RICE stands for Reach, Impact, Confidence, and Effort. For simplicity, I assign each variable with a score from 1 to 5. To prioritize experiment ideas in our backlog, I use the formula: (R * I * C) / E. On average, the higher the score, the higher the priority.

The goal is not precision, but consistency. As long as the same methodology is applied to every idea, then I am weighing everything consistently. As my experience and intuition grow, the consistency will also evolve.

I have refined the framework to be A-RICE, which includes core assumptions ("A") and distinguishing between iterative/investment features and "big bet" features within the "RICE" part.

Align on Your Core Assumptions

Assumptions are the "educated guesses" made when scoping features or experiments. They serve as a north star for decision-making and trade-off discussions, particularly when tied to engineering, product, and design implications. Aligning leadership on assumptions helps mitigate last-minute changes in complexity or feasibility. As with axioms in mathematics or the base of a skyscraper, everything builds upon solid foundations.

I’ve found these steps useful when articulating assumptions:

What are you taking for granted when driving product decisions? Write it out.

For each assumption, write out the rationale for why you and the team decided to have that assumption. (Note: Not all assumptions have rationales, sometimes both are valid and it’s a matter of choosing which assumption, see below for an example).

For each assumption, write out the implications that this assumption has on engineering, product, and design. What decisions have been made in the past that support or contradict this assumption?

Write out the benefits and risks (if applicable). Seek input on these assumptions from stakeholders, and revise as necessary.

Once everyone is aligned, choose the key assumption for the upcoming launch. If results differ from expectations, revisit the assumptions from the previous launch and determine which ones should change for the upcoming launch

Example of Writing Out Assumptions: Trial Extension Incentives

We recently tested extending the days of a user’s free trial based on if they completed certain product actions. We had a spirited discussion about whether we should highlight specific features for a user or allow them to browse for the best fit. The essence of the question really wasn’t about the feature, but rather the underlying assumption:

Do we want our users to have the perception that features are easy to set up?

Do we want our users to pick the feature that best suits their needs?

The nuance: not all of our features had intuitive setup experiences, and users would tragically abandon the feature even if it aligned with their needs! Because we did not have the resources to improve the setup experience of these features at the time, we had to make do with the current state of our features.

Whether the assumption we chose was the right decision is not the point, the truth can be discovered through user research and A/B testing. The real point was to agree on what should be included in our v1 vs postponed to a future version. In product, clear-cut answers are rare, and decisions entail both benefits and risks. To navigate this ambiguity, open and honest conversations about trade-offs are crucial, starting with aligning on the core assumptions driving experiment decisions. Even if the results are unexpected, the team can then revisit the assumptions to see what should be changed for the next iteration. Over time, your team will learn and your assumptions will become more accurate!

There are trade-offs to choosing either assumption. The goal is to agree on an assumption, knowing later that we can revise the assumption if the results say differently. In the long run, timeboxing alignment decisions on assumptions also saves you time because you are liberated from decision paralysis so you can focus your time on moving the project forward into the next phase instead of being stuck debating.

How to Use the RICE Framework*

*The RICE framework works best for iterative or investment ideas. They do not work as well for Big Bet/Moonshot ideas. See the “Confidence” section below for more elaboration on Big Bets.

Reach - How many users will experience your feature or experiment?

Reach is how many users your experiment or feature will affect. Consider the time frame and specify if the reach is based on users during an experiment window or when the feature is launched to general availability (“GA”). If the latter, be clear on how long after GA - 1 quarter? 1 year? Up to you! The importance is being clear about your time frame.

If you are at an earlier stage company or are unsure about the reach, you can assign a relative score (1 - 5) based on the impact on different product surfaces or expected traffic. RICE isn’t meant to be precise, it’s just one tool (among many) to help provide structure when making decisions.

Additionally, it’s also important to determine the eligibility criteria for users to experience the feature and analyze historical data to estimate the number of eligible users.

Example:

For free trial experiments, we initially limited eligibility to a subset of high-intent users. We then wanted to expand eligibility through in-product notifications. To understand the new “reach” of this experiment, we had to calculate how many more incremental users would be eligible for this experiment and estimate how much lower the conversion rate would be for the expanded pool of lower-intent users, based on their historical behavior. We were making an educated guess on if the expanded eligibility would offset the lower intent-driven conversion rate.

Impact - What is the incremental lift on your company goals?

Impact can be measured quantitatively or qualitatively. Before measuring impact, it is important to understand how your project aligns with company goals and priorities. If your project does not directly contribute to company goals, consider finding another project that has a clearer impact to ensure resource allocation and prioritization.

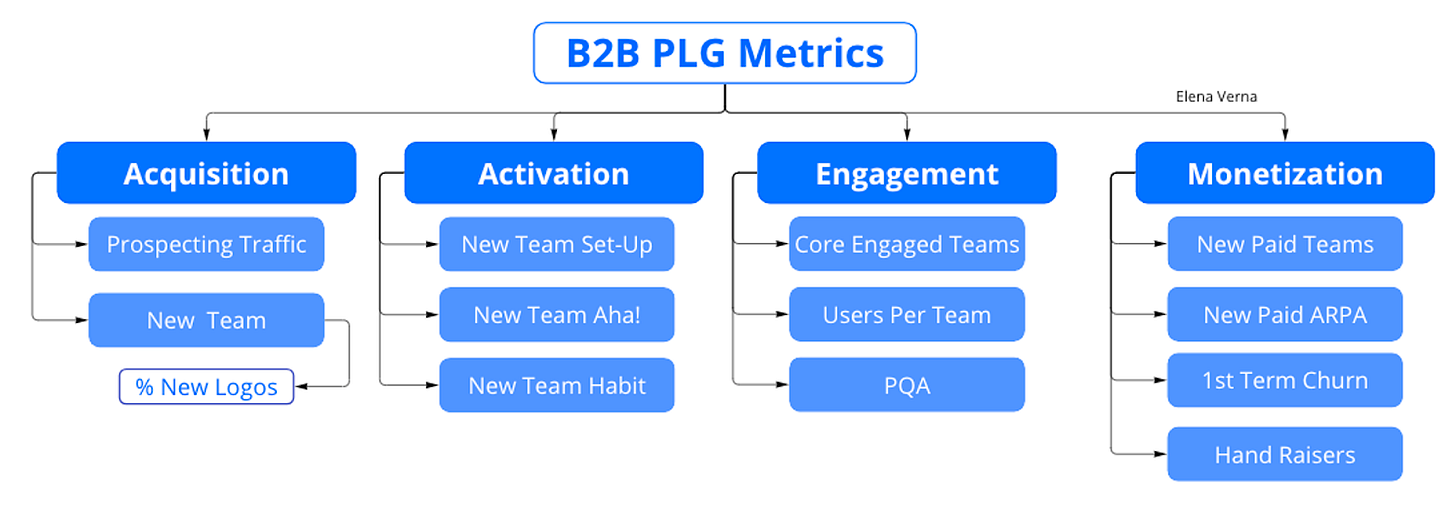

Oftentimes, the company OKRs are related to revenue. To quote Elena Verna, “Revenue is not a metric, it’s an outcome.” It can be challenging for PMs to tie their experiment or feature impact to revenue. Instead, I advocate that you tie your project impact to forward indicators that are predictive of revenue (or any other outcome metric that is a company goal). Elena Verna's article provides examples of forward indicators for B2B PLG companies, which can serve as a helpful starting point for identifying relevant indicators.

Once you choose a forward indicator, look for past experiments or feature launches with comparable user traffic or user experience to establish a baseline for potential impact. If historical examples are not available, you can refer to industry benchmarks and resources like Lenny's Newsletters, which provide insights on key metrics such as activation rate (among others).

However, measuring impact may not be applicable in the case of Big Bet or Moonshot ideas. These projects are high-risk and high-reward, making it challenging to accurately gauge their impact. Because even if a Big Bet does have the potential to be high impact, how confident can you be that this Big Bet will work? Oftentimes, this “confidence” doesn’t actually come from you, but rather, what the company leadership’s risk appetite is at the current time you are working on a Big Bet idea.

Confidence - It either comes from you or company leadership

Confidence revolves around your certainty regarding the expected impact of the project. In the spirit of stating assumptions: to have confidence, is to also implicitly assume that you have past evidence to help inform your certainty. Confidence applies best to iterative or investment projects, where there is past precedent or competitor comparisons of what the results are. For Big Bets at the team level, it’s okay if there is less historical precedent. It’s less about precision and more about synthesizing the user research and evidence that suggest this Big Bet might work.

However, to get confidence for Big Bets at the company-wide level, my experience across industries is that it primarily relies on the risk appetite of company leadership. Drawing a parallel from my experience in investment banking, mergers and acquisitions (”M&A”) is the closest analogy to Big Bets for PMs. However, during my time at the investment bank, leadership lacked the appetite for M&A due to ongoing Dodd-Frank compliance efforts and a focus on divestitures to shed pre-2008 risky assets. The closest “acquisitive” things the company did was having minority investments in fintech startups and completing a joint venture with China. Nonetheless, a few years later, after completing the divestiture and with a booming economy, the company embarked on an acquisitive spree, acquiring an equity platform company and a retail brokerage within 2 years of each other.

When company leadership is risk-averse, no amount of pitch decks and detailed analyses will sway their decision-making. As to how to get company leadership in the mood for company-wide Big Bets - the reasons vary and often depend on where the company is in its lifecycle. There are times when a company has created a cash cow and is in its “comfortable” phase where maintaining the status quo is most important. There’s nothing wrong with that in the short-term (as long as the company doesn’t get complacent in the long run). There are also times when companies experience technological shifts or increased competition that necessitate taking bigger swings to differentiate themselves.

In my investment bank’s case, it was because of macroeconomic factors as the company was still recovering from the 2008 financial crisis and had to sell risky assets before it could focus on large acquisitions. Regardless of the company’s circumstances, it's important to recognize that these forces are largely beyond your control. The best thing you can do is to trust your company’s leadership, who have a higher vantage point of the business and industry than you, to make that call. Working on a Big Bet often comes down to being in the right place at the right time.

Effort - It matters a lot. Be realistic about what your team can accomplish and if the impact is worth the effort.

In M&A, investment bankers think through “impact” based on the projected revenue gain or cost efficiencies, known as “synergies,” expected from a deal. However, bankers are not compensated for the “effort” required to make an integration successful since that happens after the transaction. Rather, investment bankers are paid a percentage of the transaction value. I suspect this is one, among many, reasons that most M&A deals cause dilution and the synergies very rarely fully materialize.

However, as a PM, it’s crucial to not be like investment bankers when it comes to assessing effort. Effort matters, a lot. Regardless if it’s an iterative, investment, or Big Bet, think through the ROI. ROI is measured based on expected impact over effort. In a tight macroeconomic environment, which we are in right now, ROI matters even more as resources are constrained and the cost of “misprioritization” is more pronounced.

So for any given project, what is the level of effort required by engineers, designers, researchers, and all of your cross-functional teams to get this project shipped? I like to measure this in terms of total engineering and design weeks. For example, if it would take 2 engineers 7 weeks of time - then that's 14 engineering weeks. The same methodology applies to design as well.

Since our team does quarterly planning, each engineer or designer has 12 weeks of possible work time. We then subtract weeks for PTO, on-call, incoming requests, and tech debt. The remaining weeks left are the time your team actually has to do work. For example, this typically leaves each engineer with 6-8 weeks in a quarter to do new product work. Thinking through our team’s time over collective weeks has helped us contextualize the impact and effort of each project.

To visualize the work across cross-functional teams, my team utilizes Asana's timeline tool, which helps map out engineering and design weeks. I have also used a simple Google spreadsheet in the past to map out the work as well.

Conclusion - Evolve the framework!

Effective prioritization is one of the key value drivers that PM brings. Since PMs don't code or design, one of the most impactful ways to contribute is by fostering alignment and shared goals among cross-functional teams. It's important to adapt and customize the prioritization framework, such as the A-RICE framework, according to your specific needs. This framework serves as a guide to help structure priorities and is just one of many available. I'm sharing what has personally helped me as a PM, but I'm eager to hear about other frameworks or advice you have for prioritization. Feel free to share your thoughts below!