From Finance to Product: Conducting User Discovery Interviews

What made you excel in the past might not work in the future.

Introduction

When I was in finance or business operations (“bizops”), I focused on client and investment recommendations. My managers praised my ability to quickly synthesize information into a clear recommendation and extract valuable insights during expert calls. When I transitioned to product management, I thought these skills would carry over, and approached my product roadmaps focusing on what we should be building and validating these ideas through user interviews.

However, I soon learned that this approach was incorrect. I was approaching my interviews with a fixed recommendation in mind. I filtered for what I wanted to hear and didn’t capture the nuances that the user said. I failed to ask questions confirming if the user actually had the problem our solution aimed to solve.

Instead, I should’ve used the discovery interview method - part of a category of user research called “generative research.”

Generative research is the research you do before you even know what you’re doing. You start with a general curiosity about a topic, look for patterns, and ask, “What’s up with that?” The resulting insights will lead to ideas and help define the problem you want to solve. - Just Enough Research by Erika Hall

I quickly realized that many of the skills that made me successful in investment banking and bizops were precisely the wrong things to apply to learning from our users. In this article, I will share how I “unlearned” habits from finance and bizops to improve my approach to user interviews so you don’t have to repeat the same mistakes I did.

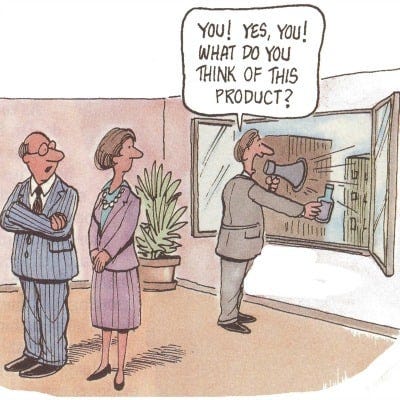

How I approached user interviews incorrectly and why

An example of “recommendation-centric” thinking in my early PM days: I worked with my designer to create a prototype for our idea related to writing lessons. I conducted UserTesting sessions for feedback on the prototype and received positive feedback that users could see themselves using the prototype if we offered this as a permanent feature. Ecstatic, I told my team leadership about the results. However, they expressed skepticism about the results, and we ended up not prioritizing the project. Later on, I received feedback on the mistakes I made while conducting user testing sessions:

I was going into these sessions with a solution in mind (the prototype) instead of focusing on how much our users even cared about the problem.

I was conflating a discovery interview with a usability test interview. Our users’ responses were based on how easy the product was to use, not necessarily if it was the right problem that solved their needs.

My journey to getting better at interviewing users

I felt disappointed after receiving the feedback, especially since I had spent so much time reviewing the user testing sessions and synthesizing the results, only to discover that the test I set up was flawed. I was determined to avoid repeating the same mistake, so I spent the next 9 months reading and teaching myself about user research and product management.

Through this learning process, I learned that asking questions to users to understand their problems differs from the questions you ask on a GLG or AlphaSights expert call or to a client during a due diligence process. Expert calls sometimes charge $1,000/hour, so you are incentivized to get an answer and relevant insights as quickly as possible. In a due diligence process, the outcome is binary: you either proceed with the transaction or don't.

However, in a customer conversation, you shouldn’t approach the interview with a solution or outcome already in mind. You are there to understand what problems users have and why it's a problem.

You aren't allowed to tell them what their problem is, and in return, they aren't allowed to tell you what to build. They own the problem, we own the solution. - The Mom Test by Rob Fitzpatrick

I found the advice in the book, The Mom Test by Rob Fitzpatrick, to be very practical and helpful. I could immediately apply the advice to user interviews I was conducting. In The Mom Test, the author emphasizes three guiding principles when conducting interviews:

Ask specifics about your user and their past behaviors. Avoid asking generics or opinions about the future.

For example, in our prototype idea, we showed a prototype before validating that users had the problem. Instead of asking users, “Do you see yourself using this in the future?” I should’ve asked, “When was the last time you actively worked on improving your writing? How long did you spend on it?”

Don't ask leading questions or fish for compliments

For example, avoid asking, "Do you think this is a good idea?” Most users, when confronted with this question, will be polite and say "yes,” or some variant of “not right now, but maybe later,” when really they mean “no.”

Talk less and listen more to your users' lives. Learn as much as possible about your user’s goals, needs, and realities (not the reality your company wants it to be).

Applying these principles required me to “unlearn” my training in investing and bizops. In those fields, there was always an expectation to “sound smart” when on an expert call or presenting a recommendation to a client, your Managing Director, or an investment committee.

Interviewing users, on the other hand, requires the opposite. It’s less about “sounding smart” and more about “acknowledging what you don’t know.” It’s essential to approach every user interview with curiosity - digging deeper into the “why” and understanding the root cause of what about the user’s life or experience motivated them to respond the way they did.

How I learned from my mistakes and approached user interviews differently now

I applied what I learned to my next project: implementing and improving our free trial program. I wanted to avoid the mistake I made previously, where I came in with solutions in mind before fundamentally understanding what motivates our users and how they spend their time.

I conducted several dozen user interviews with free trial participants who canceled their trial to understand why they canceled. (Because of limited time, we focused on cancellations and planned to interview users who upgraded after the free trial at a later date). Questions I asked this time were open-ended and aimed to understand the broader world of the user and their writing habits:

Tell us about the writing you worked on when you saw our free trial offer.

How often do you write this type of work?

Is there other writing you did in the past where you used our product? What were they? Why didn’t you feel the need to upgrade back then?

What motivated you to sign up for a free trial?

Was there a moment when you felt a difference between paid and our free version? If so, what was the context?

What were you disappointed by our paid product?

What made you decide to cancel?

What would have to be different about our product for you to upgrade again?

Before interviewing users, I thought that price was the main reason users chose to cancel. However, through interviews, I realized that “price” was more nuanced - that beyond the actual number, it was also the user’s perception of the value our paid product delivered to address their needs. I learned that some users encountered long lagging times interacting with our product which added more stress to their writing process. Other users didn’t see a significant enough difference between the free and paid version. Still, when I dug more, I learned that the root cause might be less because of the “difference” and more because the trial duration might not be long enough for them to experience all the differences.

I wouldn’t have realized these nuances of how users viewed our paid product until I conducted the interviews through the “discovery” method. With a more nuanced understanding of our user problems, our working group could more effectively narrow in on the problem we wanted to solve for our users who experienced a free trial. We took our narrowed user problems and did a very productive brainstorming session where we thought of experiments we could test to validate the solutions we generated together. (For brevity, I am purposely brief on how we synthesized user insights into a product roadmap. I can discuss this synthesis process in a separate article. In the meantime, I recommend reading Continuous Discovery Habits by Teresa Torres, as I applied her advice directly to our interviews and brainstorming sessions.)

Conclusion

My first few user discovery interviews were terrifying. My heart raced right before every interview because I was nervous. All of the tips on how to correctly interview users that I read from The Mom Test, Just Enough Research, and many other product management books felt overwhelming. How was I supposed to condense all of the advice into one short 45-minute user interview session? At first, I stumbled and mumbled through my questions and follow-ups. As time passed and I gained experience, interviewing users became easier. The advice and tips I initially had to memorize are now second nature.

If you're uncomfortable interviewing users, don't worry - I've been there too, and still feel that way sometimes. But over time, interviewing, like any other skill, gets easier and feels more natural with practice. I am by no means an expert yet on user interviews, but I now feel comfortable conducting interviews by myself if I’m not able to get resourcing for a user researcher.

Remember: when conducting interviews, approach them like a conversation and maintain an open mind and curiosity about your user's life and motivations. This approach will help you prioritize the correct user problems and develop an intuition for what your users care about in the long run.